Endarkenment

Arkadii Dragomoshchenko

Edited by Eugene Ostashevsky

Translated by Lyn Hejinian et al.

Wesleyan UP (2014)

Read by Andre Furlani

The Russian modernist poet Osip Mandelstam declared in the epochal “Conversation about Dante” that “to speak means to be forever on the road”: “When we pronounce the word ‘sun’ we are, as it were, making an immense journey which has become so familiar to us that we move along in our sleep” (Mandelstam 2004 115). In uttering a word, “we are living through a peculiar cycle” rather than conveying an “already prepared meaning” (ibid). The condition of speech is flux: “All nominative cases should be replaced by datives of direction. This is the law of reversible and convertible poetic material, which exists only in the performing impulse” (153).

This performing impulse drives the verse of Mandelstam’s canny descendent Arkadii Dragomoshchenko, whose every word and phrase is a volley. After attending theatre school in Leningrad – Mandelstam’s “Petropolis” – in the 1970s, he began to collaborate on samizdat periodicals, from type-setting and editing to contributing poems. With Mikhail Iossel, he belonged to a Leningrad underground that perpetuated the proscribed legacy of the stunning early twentieth century Russian avant-garde in which Mandelstam figured, along with Velimir Khlebnikov, whose zaum “beyonsense” experiments in a hermetic non-referential sound poetry rivalled Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons and the “parole in libertà” of Futurism. Invoking Khlebnikov directly in “Nasturtium as Reality,” he writes: zaum returns as conclusion what it has absorbed/ and dissolved into pure plasm each day” (121).

Thus, despite the Soviet suppression of Formalism, Constructivism, Cubo-Futurism, Acmeism, Structuralism, and their numerous postmodern progeny, the plasmic poets of the Andropov era were well-prepared for the arrival of the American language poets. With no language between them but the buoying beyonsense of poetry itself, Lyn Hejinian and Dragomoshchenko embarked on a friendship in Leningrad in 1983 that, with the Glasnost thaw, issued in the 1989 poetry seminar attended by Ron Silliman, Barrett Watten, Michael Davis, and Hejinian. The next year the latter collaborated with Elena Balashova to produce an English translation, Description, and with the collapse of the Soviet Union the poet was free to tour the United States and to accept teaching gigs at American universities.

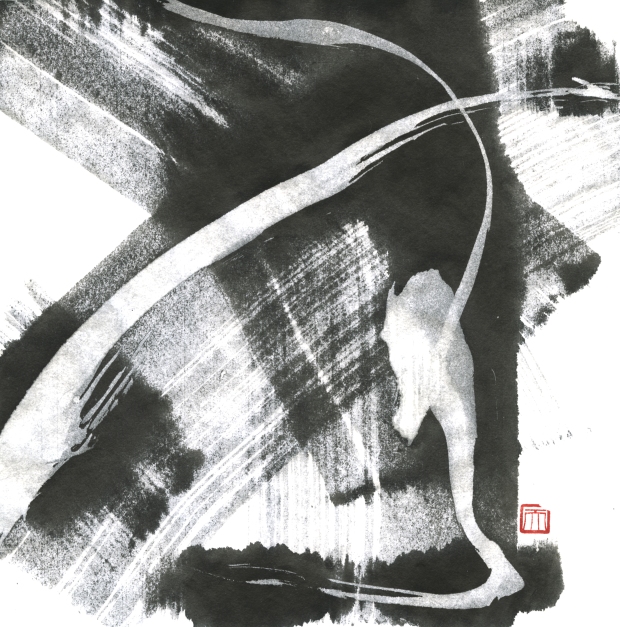

Endarkenment is the fifth volume of Dragomoshchenko’s poetry to appear in English, in a handsome bilingual edition that includes a capsule biography, a bibliography of his works, photos, a preface by Hejinian and an illuminating essay by Ostashevsky. A photo of the jocular chain-smoking poet on the hood of a Lada balances the striking dust-cover reproduction of Dragomoshchenko’s grainy, grim self-portrait as an emaciated inmate peering from the aperture of a gulag-like door, an image projecting the poet’s literary marginalization and precarious political status. “Under Suspicion” was the title of a collection excerpted in the present volume. Endarkenment indeed, and yet, far from prolonging the note of incarceration, the poems convey an impish, convivial liberty from cant, coterie, and prosodic convention. With more joy than righteous indignation he releases words and phrases from the Bastille of Soviet aesthetic mandates and ubiquitous institutional mendacity.

“There they are again, the signs that have lost their meaning,” he writes (43), and these are equally the empty verbal ciphers of Structuralist linguistics and the bankrupt heraldic symbols of Soviet supremacy. “The perspective should have changed,” he declares with an eye to the late-Soviet stagnation, adding, with a nod to Charles Olson’s “The Kingfishers”: “And it changed” (87). This poem can be wry indeed about the era, and perhaps clairvoyant about our own: “Everything was in decline./ Even the talk about everything being in decline” (87). The poet refuses elegy as well as satire in favour of the erratic, the uncanny, the illegible. The verse is in flight from the meekly paraphrasable, for he agrees with Mandelstam that, where one finds paraphrase, “there the sheets have not been rumpled; there poetry has not, so to speak, spent the night” (2004 104).

With an ear to vacuous official oratory, Dragomoshchenko attempts, at the level of the phrase, what Paul Celan, Mandelstam’s unsurpassed German translator, achieved at the level of the word, the rehabilitation of a national language implicated in the outrages of despotism – “the thousand darknesses of death-bringing speech,” the Holocaust witness Celan called it (Celan 1983 38: hindurchgehen durch die tausend Finsternisse todbringender Rede). “These words still remained/ as though they’d not been pulled out by the root,” Dragomoshchenko observes with some amazement (89). The sterility of official discourse threatens to disable all living speech:

We often fell silent mid-word that autumn.

A spectral series of things, of which

not one was able to become a thing,

but only a rut of meaning that

will never need untangling in the moisture of breath. (93)

A poet’s task, says one who alludes frequently to Ludwig Wittgenstein, is not to declaim authoritatively but to “respect the poverty of language,/ respect impoverished thoughts” (105). Dragomoshchenko develops by copiousness what Samuel Beckett sought in “lessness,” which the latter described in a 1959 letter as the attempt “to find a syntax of extreme weakness, penury perhaps I should say” (Beckett 2014 211).

Dragomoshchenko finds in this miraculously productive debility a lyric logic of exchange and conversion that, free of morbidity, stoically affirms decay and limitation:

More likely, someone really did show weakness,

because there is only substitution, the slippage of histories,

syntax of the alternation of forces, little shards on the floor,

rotting irises, rats. (81)

Relying on his cherished “rhetoric of accumulation” (119), the poet stirs the sediment of Van Gogh’s irises, T.S. Eliot’s rats, de Saussure’s signifier, and Beckett’s infirmity, and he holds this cloudy beaker to the light. You will be surprised to see how it shimmers.

Dragomoshchenko was a dissenting poet rather than a poet of dissent. The political enlistment of poetry, either by the salaried scribblers of Politburo anthems or by their strident versifying denouncers, is derided in a mock-address to Cavafy:

I banished the rhapsode from government. Why?

Well…you know, this novelty, the photocopier

that finally arrived from Corinth,

it can replace rhapsodes entirely. (103)

In “To a Statesman” there is liberty in the form of a grand refusal of all political formulas; “protocols turned to dust in concrete castles” (32). The speaker of the poem shares with the protagonist of Vladimir Nabokov’s dystopian novel Bend Sinister childhood recollections of a classmate who went on to service in a draconian regime. Like Mandelstam’s Petersburg classmate Nabokov, Dragomoshchenko regards a formally self-conscious virtuosity as defiant affirmation of personal moral freedom. The discrete phrases pick up speed among contiguities and kinships that deviate abruptly into new relations, disdaining the artistic protocols that determined admission to the Soviet Writers Union and thereby to publication. The connections that count are irrefutably embodied, indeed labial, like the lover’s shoulder tattoo he kisses “so that word may open to word” (55).

Even as it disrupts the semantic markers of historicity, temporality is the medium of this poetry that registers fluctuation at the very level of composition. To Hejinian, Dragomoshchenko “was a poet in the tradition of Lucretius, following atoms of sensation into the crinkled atmospherics of thought” (x). For this task, no simple mimetic reproduction of particulars would suffice; words are primary pigment and a word is a living thing, with “the moisture of breath,” as he says:

We will remind you: reflections were of little interest to anyone,

to see – even now – means to become what you saw.

Who didn’t we become…contemplation of time

turned into the most delicate sand

running through a woman’s fingers,

which we also had the occasion of being,

as well as other things: decay, sod,

the formula of running, in which there also hid the cause

of what could not be shared with the dead,

belonging as it did to everyone in equal measure. (75)

In a letter to Hejinian that she quotes, Dragomoshchenko relates a euphoric vision of “the world whirling in a beautiful absence of will, in which glimmers an unintelligible belief in everything, to the point of idiotic tears, when one sets out for milk in the morning and stops at every step” (xi). In “Nasturtium as Reality” he equates the verb with the idle walker’s successive, vulnerable, contingent perspective, which accumulates consonances of chance and intention: “thanks to the verb, meaning more often/ aimless walking along the sand” (135).

Mandelstam compares speech to a congested river and the poet to one darting from one hithering-thithering Chinese junk to another to light on the opposite bank (see Mandelstam 2004 105). Even in translation one can make out the fleet, limpid finesse and determination of Dragomoshchenko’s sprint from one end of a line to another. He directs an implicit protest against linguistic complacence and the ideological conscription of language, and he celebrates the incantatory traffic of signifiers between speakers and, as in the case of this captivating volume, between languages as well.

“Blessed is he who calls the flint/ the student of running water,” writes Mandelstam (Mandelstam 2004 50), and so is Dragomoshchenko blessed. “What is said is not to be said again” (135), simply because it cannot be: words are living through a peculiar cycle. In dizzying desultory strides he crosses every divide, almost Whitmanesque in his invitation to a blurring of identities: “you breathe out:/ you sign for me: dragomoshchenko” (95).

“To examine the nature of resemblance, without resorting to symmetry” (21) is the credo of a poetry that spots kinships and juxtaposes unlikely consonances without imposing a transcendent equivalence. The phrase is from the aptly titled “The Weakening of an Indication,” which ends on a note of strong weakness for the union of contraries: “The narrow sail of the sand” (23). This appropriately fragmentary sentence contains Dragomoshchenko’s special emblem (23), wisps of granular wind-borne cursives that trace memories of the sea across a desert.

CITATIONS

Beckett, Samuel. The Letters of Samuel Beckett, Volume III. George Craig, Martha Dow Fehsenfeld, Dan Gunn, and Lois More Overbeck, eds. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2014.

Celan, Paul. Der Meridian. Frankfurt am Main: SuhrkampVerlag, 1983.

Mandelstam, Osip. Selected Poems. Clarence Brown and W. S. Merwin, trans. New York: New York Review of Books, 2004.