Interview of Marianne Apostolides, author of the novel Sophrosyne

Questions and introduction by Rick Meier

Marianne Apostolides’s beautifully unconventional new novel Sophrosyne (BookThug, 2014) follows Aleksandros (or Alex), a philosophy student writing his senior thesis on the Socratic virtue of sophrosyne — a Greek word for which there is no suitable English translation. Alex is a handsome youth: an accomplished athlete and a promising student (he is eventually nominated for a Fulbright grant); but his personal and intellectual endeavors remain haunted by the memory of his now-absent mother, the mysterious ‘you’ to whom the novel is addressed: a belly-dancer whose stage name is Sophrosyne.

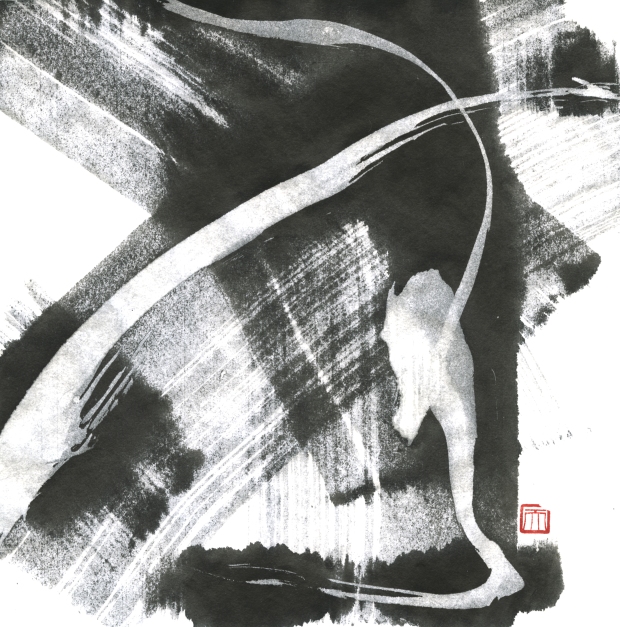

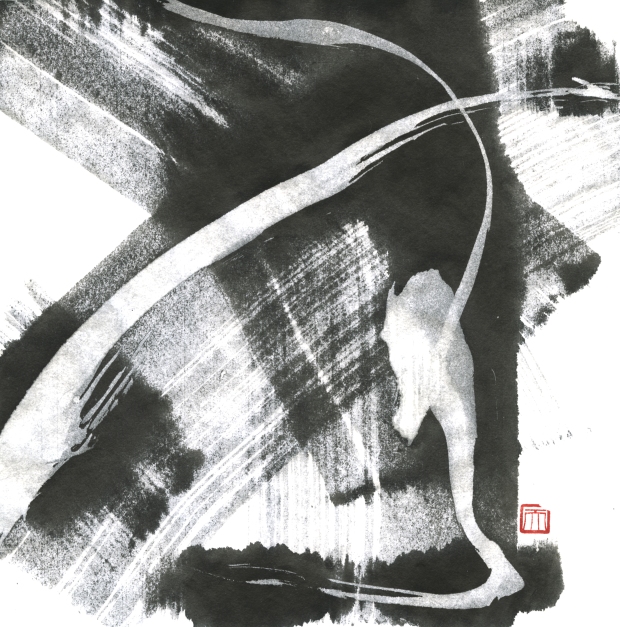

While the initial pulse of the book is established by Alex’s need to understand his past, the second half is shaped by a new drive: Aleksandros’ burgeoning relationship with Meiko, a Japanese-American student he meets in an art gallery. Through this relationship, the novel breaks open. Alex’s self-enclosed thoughts are challenged by Meiko’s Eastern-influenced understanding of desire, vitality, and sophrosyne. Meiko’s perceptual framework quietly exists throughout the book through five works of calligraphy that precede several chapters. These works are not introduced; they simply appear in the book, silent and beautiful, urging readers to be patient — to wait for the meaning to be revealed.

Lyrical, darkly erotic, and bursting with ideas, Sophrosyne is a novel about the pursuit of wisdom itself, and the ways we reach out for understanding — motivated not always by an inborn love of truth, but by a need to exorcise dark memories and unspeakable longing.

I caught up with Marianne Apostolides on the eve of the Toronto launch of Sophrosyne to talk about some of the ideas behind the novel, the process of producing a fifth book, and her collaboration with painter/calligrapher Noriko Maeda.

I’ve heard Sophrosyne described as a “posthumanist novel.” Can you tell us a bit about how you first became interested in posthumanism, and how those ideas found their way into the book?

A friend of mine, who’s a curator of photography, first mentioned the theory to me while we took in a show at MoCCA. Photography is playing with the concept far more than fiction; even if photographers aren’t labeling their work ‘posthuman,’ the aesthetic/ ethic is moving away from postmodernism into a new perspective of the ‘human animal’ and our relationship to self, society, nature and the divine (however loosely defined). My friend suggested I read Donna Haraway’s recently-published book When Species Meet (University of Minnesota Press, 2007). From there, I began to read more; the theory allowed me to crystallize and comprehend some of the changes I’d already sensed within the art world — and within the ‘real’ world — namely: how do we define ourselves, as the human animal, in a world in which ‘God’ is absent, technology is omnipresent, and the global environment is in a state of collapse…. These are not the coordinates that gave rise to modernism/ postmodernism. Frankly, they’re not the coordinates that gave rise to humanism, either, with our sense that mankind is above all other beast — graced by God with a conscious mind, which allows us to manipulate/ replicate laws of nature.

I need to be clear, though: this book is not didactic or dry. Hardly… It’s actually an incredibly sensual exploration of a messed-up guy and his relationship to women — including his mother.

But, within those relationships, I’m also exploring the meaning of mankind in a ‘posthuman’ age. More specifically, I’m examining the interaction between our conscious mind and our physical appetites/ desires. Those explorations arise naturally in the novel, since Alex is an undergrad studying philosophy. Certain conversations flow smoothly into the realm of ides, especially as he talks with his thesis advisor — a guy who’s a bit of a prick, and whose dry sense of humour lends some lightness to the novel.

Oh, and then there’s the sex scene centered around Plato’s Phaedrus, and masturbation to The Iliad, and a conversation about posthumanism conducted with a dead woman. Stuff like that.

Do you have a least favourite English definition of sophrosyne? A least favourite?

I think ‘self-control’ and ‘temperance’ would be my least favourites: ‘self-control’ because it seems like a moralistic denial of all desire — as if desire were inherently wrong; and ‘temperance’ because it’s such an insipid word….

As for favourites: I like ‘self-restraint,’ because the word ‘restraint’ is inherently raunchy — containing the sense of seduction which sophrosyne must encompass. Sadly, ‘self-restraint’ isn’t a great definition because, in true sophrosyne, desire isn’t lashed as much as held within potency/ balance…. ‘Rightness of mind’ is the most literal translation of the Greek word, but then we arrive at the question: what is ‘mind’? It certainly isn’t cognition/ cogitation…. Sophrosyne shares a root with the words frantic, frenetic, and schizophrenic: these are what happens when the ‘mind’ is not in ‘rightness.’

Have you noticed I haven’t answered your question?

If you want a preferred translation, the one I like is ‘self-possession’: the self in possession of its self — as it relates to the body, to thought, to the external world and its own desire….

Can you tell us a little bit about why you wanted to include calligraphy in the novel?

Sure. This novel is more concerned with language/ thought — in a physical, immediate sense — than it is with plot. As a result, the reader isn’t carried along on the surface of prose; instead, s/he’s brought inside a viscosity/ density/ weirdness….

Poetry can do that exceedingly well, but prose lacks the tools at poetry’s disposal. One of those ‘tools’ is the rupture of syntax. Well, I borrowed that technique, adapting it for the novel — mainly through my use of ‘and’ ‘but’ and ‘because’ at the start of sentences, leaving the reader to wonder where the referent of these words might be. This interruption of causality is essential to the book — and to the questions it wants to explore.

The second tool is what led me to calligraphy ….

Poets engage in visual play, using the expanse of the page. If they want, they can surround the words by blankness, allowing the language to radiate/ reverberate/ ripple. Well, novelists don’t generally have that ability. We need to send forth a stream of words — tens of thousands of words relentlessly driven in straight lines across the page! Depending on what you’re doing with the form called ‘novel,’ that can be just fine. But in a novel like Sophrosyne — one in which the reader must ride atop this monstrous, living thing called language — the text must provide a way to extend the reader’s attentiveness across the words. Visual images allowed me to do that.

Although I knew I wanted to break up the text with images, I wasn’t sure what those images would be, or how they’d be integrated into the narrative (…not another facile imitation of W.G. Sebald, please…). After over a year of working on the novel, I finally discovered that Alex’s love interest was a Japanese woman named Meiko. Immediately, I knew she’d be a painter/ calligrapher; the visuals suddenly became organic to the story.

You write that Noriko’s calligraphy “became the axis around which [Sophrosyne] took form.” Can you tell us a bit more about that?

For over three years, I struggled with the structure of the book. I’d written many scenes between Alex and his mom, each of which portrayed the increasingly disturbing intensity of their relationship. The scenes had energy, but the book, as a whole, was dead — sealed inside this dark, erotic relationship. That sense of enclosure was exacerbated by the novel’s main constraint: namely, that text consists of Alex’s thoughts, as directed toward his mom. (I.e., the second person ‘you’ infuses the narrative.)

This constraint became a challenge for me, as a writer: how do I introduce a new character — giving her depth and pulse — without writing really bad, expository back-story. (…We’ve all seen those moments in Hollywood movies; you can almost hear the music swell….)

Anyway, the solution to this challenge was calligraphy….

I soon realize I’d precede certain chapters with a calligraphic image, inserting the artwork before Meiko is introduced as a character. Without explanation, the reader is shown beautiful works of calligraphy. S/he needs to take these images as given, trusting that their significance will become apparent, in time. Only slowly do readers realize this artwork relates to Meiko; by then, they’ve already come to know this woman through the works she’s created.

When I toyed with that structure, the book became more balanced — not weighted so heavily toward Alex and his mom, or toward Greek philosophy/ thought. In other words, the visual language of Japanese calligraphy brought the book, as a whole, into tension with itself — not only the tension among the characters, but also among the various ways of perceiving the world.

You say that Noriko Maeda’s description of mu, 無— translated as ‘nothingness’ — gave you a new perspective on sophrosyne. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

After contacting Noriko Maeda — asking whether she’d be willing to include her work in my book — I was invited to her home. She said we could discuss the book; I could then explain, specifically, how her calligraphy was going to be incorporated.

The problem was: I didn’t have a clue how my (unruly) manuscript was going to use the works of a master calligrapher…. The book was still two years from being complete; its structure was still evading me. Or, to be more accurate, its lack of structure was mocking me…. This was a very dark time in the five-year process of writing this book….

And yet, I arrived at the home of Noriko Maeda, a world-renowned calligrapher. Somehow I had to take my place as an artist beside her. She made it easy for me; her artistic intelligence is sparkling and somewhat devilish…. Anyway, we shared a home-made lunch then got to work. I suggested several words that might be rendered as Japanese kanji/ calligraphy. Each word was taken from a fragment of Japanese philosophy — fragments which related to my all-too-vague sense of the concept sophrosyne.

As I suggested English words to translate/ depict, Noriko would wave her hand, as if swatting away a mosquito. ‘No, no: that word isn’t alive. I can’t do anything with that word….’

Then I mentioned ‘nothingness’ — a prominent concept in Japanese philosophy. This got Noriko interested…. She showed me a series of paintings she’d completed several years before, all of the same kanji: mu, 無, ‘nothingness.’ These paintings were varied in tone, in colour, in smear, sensation…. I loved them, but ‘love’ is rarely the basis for the structure of a novel…. Then Noriko showed me the kanji ‘nothingness’ in its ancient script, before it evolved into the form it takes now. It appears as a pictograph of an old-fashioned scale — the kind in which two plates are suspended on either side of a central pole.

This, Noriko said, is the original image of nothingness: not non-ness, but potency, balance — where all is held in abundant stillness….

Once I saw such a clear depiction of the concept, I sensed the ways in which ‘nothingness’ and ‘sophrosyne’ informed each other. They are not synonymous; instead, they are a dynamic coupling.

What, if anything, has publishing your fifth book taught you about writing?

1. Writing does not ever get easier…. And I mean ever.

2. Writing is not sane/ healthy.

3. Oddly linked with point #2: writing is a glorious way to structure a life….

4. BookThug is a welcome exception to a disturbing reality in the publishing industry: namely, that publishers usually buy a ‘product’ — i.e., a manuscript — rather than developing a relationship with an author, as BookThug has done with me…. The gruelling experience of writing this book exposed, at various points over the past five years, how utterly I rely on the trust/ respect that BookThug has given me. My writing can take substantive risks because of it; without it, my career, this book, and my life as a writer simply wouldn’t exist.

For more information about the painter/ calligrapher Noriko Maeda, please see her website: norikomaeda.com.